A History of Ecuadorian Literature – Part 1

Narrative art in Ecuador, of course, preceded the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century, in the form of indigenous folklore and religious mythology. However, the earliest example of the western narrative tradition in what had formerly been known, before the conquest, as the Kingdom of the Shyris, was novel, The Dream of Heaven, written in the 17th century by the Guayaquil-born priest, Jacinto de Evia, who nonetheless, was more well-known for his poetry.

Afterwards, it would be a full two centuries, following the war for independence from Spain, that the new country would produce its first novel, the 100-page,The Emancipated One, by Miguel Riofrío, initially published, like the novels of Charles Dickens, in installments, though formerly printed as a book in 1863.

Jacinto De Evia

Miguel Riofrío

Juan León Mera

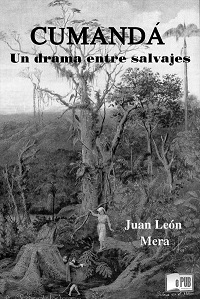

However, Cumandá: A Drama Among Savages, published ten years later is, with its more conventional length, more commonly regarded as the first “genuine” Ecuadorian novel. Very much a product of the 19th century Romantic movement, and inspired in part by the novels of François-René de Chateaubriand and James Fenimore Cooper in examining conflicts between European and native populations in the Americas, Cumandá presents a romance between a rancher’s son and the titular heroine, an indigenous beauty, who like Pocahantas, saves the life of the white European she is in love with.

Though initially very much a liberal, like his anti-clerical childhood friend from Ambato, Juan Montalvo, by the time Mera had written Cumandá, he had become a strong supporter of Gabriel Garcia Moreno, the very conservatively Catholic president of the Republic of Ecuador, and Mera’s novel, in part, served as an apology in favor the conversion of the indigenous population to Roman Catholicism.

Cumandá

Luis A. Martinez

Juan Montalvo

The Liberal Revolution of 1895, led by the President José Eloy Alfaro, which implemented progressive reforms and weakened the authority of the Catholic church, gave new impulse to writers critical of the conservative establishment, most notably Luis A. Martinez, whose most well-known novel, To the Coast, published in 1904, can be compared to the works of American writer, Upton Sinclair, during the same period, in bringing to the attention of the reading public some of the harsh realities of life for the working-class.

The book’s protagonist is the young son of a conservative, middle-class family in Quito. When the father dies, the son goes to work on a coastal plantation, and in the process, witnesses the disintegration of his family.

Two decades later, Fernando Chaves continued in the social realism genre with Silver and Bronze, published in 1927, with its depiction of the indigenous population exploited and abused by the landed gentry as well as by the local clergy.

Enrique Gil Gilbert

Joaquín Gallegos Lara

Alfredo Pareja Diezcanseco

Later on, additional writers such as José de la Cuadra and Alfredo Pareja Diezcanseco joined the Guayaquil Group, and added much to its reputation through novels and stories that challenged Ecuadorians to think about class inequality and racism.

It should be noted that each member of this collective also had additional and more personal themes apart from social and political protest.

José de la Cuadra, for example, introduced elements of fantasy in his narrative, anticipating the magic realism that would later emerge in Latin American writers such as Gabriel García Márquez.

José De La Cuadra

Pablo Palacio

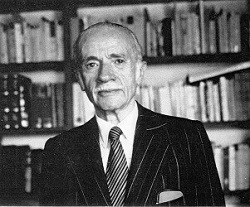

Jorge Icaza

Shortly thereafter, in 1930, the Guayaquil Group emerged, making their proper contribution to this genre. Demetrio Aguilera Malta, Enrique Gil Gilbert, and Joaquín Gallegos Lara, all based in Ecuador’s principle port city, published a short story anthology, Those Who Go Away: Stories of the Mestizos and Country People, which impacted Ecuadorian fiction for generations to come.

In keeping with their ideological principles, the group made the poor and non-Caucasian Ecuadorians the principle and most sympathetic characters, while the representatives of power — the oligarchy, the landowners, the clergy, and the constabulary — were seen in a negative light.

In addition, with its rough, working-class vernacular, and candor in matters relating to race and sex ( one story is entitled “The Half-Breed who Castrated Himself”), the book ruptured standards of decorum for Ecuadorian literature, and was regarded as scandalous among bourgeois readers.

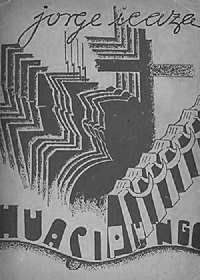

Huasipungo

However, it was Jorge Icaza Coronel’s Huasipungo, which marked a major turning point in the development of the Ecuadorian novel. Comparable to Uncle Tom’s Cabin in its didactic intentions as a condemnation of racism and exploitation, but superior as a work of literature, Huasipungo brought international recognition to Ecuadorian writing, eventually being translated into forty languages, including Portuguese, German, Italian, French, Swiss, Czech, Polish, and Russian.

The story presented in Huasipungo is bleak in the extreme in its depiction of an exploited rural indigenous class, and an avaricious, land-owning Caucasian upper-class. Icaza, a harsh critic of Ecuadorian society, does not offer a happy ending, much less any reconciliation between his haves and have-nots.

Apart from the social realists, from the late 1920s going forward, Pablo Palacio produced some of the first avant-garde fiction in the country. For example, as scholar, Elizabeth Coonrod Martínez, notes, Palacio’s novel, Debora, deals with a character, a “Lieutenant,” who “has not yet fully left the artist’s head.” It ends “because the narrator has the Lieutenant disappear (he is slashed by a paper cut), thereby neglecting traditional character development.”